Session Six - Major and Minor Prophets (2)

Introduction

The return of the exiled Jews was foretold by the prophets, but major political changes were needed before this could occur, including the fall of Babylon to the Medo-Persians under Belshazzar in October 539 BC (see Daniel 5:30, 31). Persian kings varied in their attitude toward the Jews. Under Cambyses (530-522) the rebuilding of Jerusalem was stopped (Ezra 4), but under Darius I (522-486) the second temple was completed (see Ezra 5-6). Here the post-exilic prophets Haggai and Zechariah challenged the Jews: "You live in paneled houses while God's house lies in ruins. Do something about it!"

Darius was followed by Xerxes (486-464), whose reign is recorded in Esther 1-9 (many Jews in Persia remained there during Esther's time). Following Xerxes came Artaxerxes (464-423), during whose reign Ezra returned to Jerusalem in 458 BC (Ezra 7-10), and Nehemiah followed in 445 BC (Neh. 1-2). It was in this period that the final post-exilic prophet Malachi wrote.

The book of Ezra deals with the return of the Jews as promised over 70 years before by God through the prophets Jeremiah and Isaiah. The book of Nehemiah also covers the return and rebuilding of Jerusalem after the exile was over. These men were not prophets, but their pivotal roles will be described in this session.

Return from Captivity

The Babylonian Captivity, also called Babylonian Exile, the forced detention of Jews in Babylonia following the latter's conquest of the kingdom of Judah in 598/7 and 587/6 BC. The captivity formally ended in 538 BC, when the Persian conqueror of Babylonia, Cyrus the Great, gave the Jews permission to return to Palestine. Historians agree that several deportations took place (each the result of uprisings in Palestine), that not all Jews were forced to leave their homeland, returning Jews left Babylonia at various times, and some Jews chose to remain in Babylonia - thus constituting the first of numerous Jewish communities living permanently in the Diaspora.

It is generally believed that the tribes of the Northern Kingdom (Israel) did not return and were absorbed into other cultures over the following centuries.

Aside: British Israelism teaches that Anglo-Saxons make up two of the lost tribes of Israel, one in England, the other in the United States. Followers maintain that when the northern kingdom of Israel was taken captive by the Assyrians, these tribes escaped and emigrated to the British Isles. They believe that the Anglo-Saxons were selected to rule the world and that this will be accomplished by the merger of Britain and America into one common citizenship. The late Herbert W. Armstrong and some fringe evangelical groups follow British Israel ideas. There is no historical proof for the claims.

Although the Jews suffered greatly and faced powerful cultural pressures in a foreign land, many maintained their national spirit and religious identity. Elders supervised local Jewish communities. Ezekiel was one of several prophets who kept alive the hope of one day returning home. This was possibly also the period when synagogues (*local places of worship) were first established, for the Jews in exile observed the Sabbath and religious holidays, practiced circumcision, and substituted prayers for former ritual sacrifices in the temple.

When some of those in exile returned during the reign of the Persians, the degree to which the Jews looked upon the Persian King Cyrus the Great (600-530BC) as their benefactor and a servant of their God is reflected at several points in the Bible, eg Isaiah 45:1-3, where he is actually called God's anointed.

Model of the Second Temple

Haggai

The prophet Haggai recorded four messages to the Jewish people of Jerusalem in 520 BC, eighteen years after their return from exile in Babylon. Haggai 2:3 seems to indicate that the prophet had seen Jerusalem before the destruction of the temple and the exile in 586 BC, meaning he was more than seventy years old by the time he delivered these messages. From these facts, the picture of Haggai comes into focus. Haggai was thus an older man looking back on the past glories of his nation, a prophet filled with a passionate desire to see his people rise up from the ashes of exile and reclaim their rightful place as God's light to the nations.

Haggai's prophecy came at a time when the people of Judah were extremely vulnerable. They had been humbled by their exile, hopeful in their return to their Promised Land, and then so discouraged by opposition in their rebuilding of the temple that they had quit (Ezra 4:24). Now, sixteen years later, with Haggai blaming their lack of food, clothing, and shelter on their failure to rebuild the temple, the people were receptive to his call to rebuild the temple. They had forgotten their God, choosing instead to focus on their own interests, so it was time for them to "consider (their) ways" (Haggai 1:5, 7). Nothing was more important for the hearers than to show that the Lord was at the center of their thoughts and actions.

Unlike most of the other prophets, Haggai explicitly dated his prophecies, down to the day. He gave four separate messages, the first on August 29, 520 BC (Haggai 1:1); the second on October 17, 520 BC (2:1); and the final two on December 18, 520 BC (2:10, 20). These messages encouraged the people of Judah to finish building the temple and to have hope in God for the promise of blessings in the future.

Rather than leaving them alone with the task of rebuilding, Haggai continued to preach to the Jews, encouraging them with the hope of future glory in the temple and a victory to come over their enemies (2:7-9, 21-22). According to his message, if the people would place God at the center of their lives, they would realize the future blessings that God had in store for them.

The Jews who emigrated from Babylon to their original homeland of Judah faced intense opposition, both external and internal. Ezra 4:1-5 records the external resistance to the project of rebuilding the temple. Their enemies first attempted to infiltrate the ranks of the builders and, when that didn't work, resorted to scare tactics. Haggai, on the other hand, focused on the internal opposition they faced, namely from their own sin. They had thoughtlessly placed their own interests before the Lord's interests, looking after their own safety and security without considering the status of His house.

Appearances can be deceiving. When the temple was rebuilt, there were some who remembered the former temple (since destroyed) and criticized the new one. Their focus was on the outward appearance. But listen to what God says:

"The future glory of this Temple will be greater than its past glory, says the Lord of Heaven's Armies. And in this place I will bring peace. I, the Lord of Heaven's Armies, have spoken!" (Haggai 2:9).

Zechariah

Zechariah prophesied to the people of Judah after they returned from exile (Zechariah 1:1; Nehemiah 12:1, 4, 16). Like Jeremiah and Ezekiel before him Zechariah was a member of a priestly family. And, like Haggai, his main purpose was to encourage the people to complete the rebuilding of the temple. Zechariah contains the largest number of passages about the coming Messiah among the Minor Prophets.

Jesus quoted Zechariah just before his betrayal:

Then Jesus told them, "This very night you will all fall away on account of me, for it is written: 'I will strike the shepherd, and the sheep of the flock will be scattered.'" (Mt 26:31)

Ezra

Jewish tradition has long attributed authorship of this historical book to the scribe and scholar Ezra, who led the second group of Jews returning from Babylon to Jerusalem (Ezra 7:11-26). Ezra 8 includes a first-person reference, implying participation in the events. He plays a major role in the second half of the book, as well as in the book of Nehemiah, its sequel. In the Hebrew Bible, the two books were considered one work, though some internal evidence suggests they were written separately and joined together in the Hebrew canon (and separated again in English translations).

Ezra was a direct descendant of Aaron the chief priest (7:1-5), thus he was a priest and scribe in his own right. His zeal for God and God's Law spurred Ezra to lead a group of Jews back to Israel during King Artaxerxes's reign over the Persian Empire.

The book of Ezra records two separate time periods directly following the seventy years of Babylonian captivity. Ezra 1-6 covers the first return of Jews from captivity, led by Governor Zerubbabel - a period of twenty-three years beginning with the edict of Cyrus of Persia and ending at the rebuilding of the temple in Jerusalem (538-515 BC). Ezra 7-10 picks up the story more than sixty years later, when Ezra led the second group of exiles to Israel (458 BC). The book could not have been completed earlier than about 450 BC (the date of the events recorded in 10:17-44).

The events in Ezra are set in Jerusalem and the surrounding area. The returning exiles were able to populate only a tiny portion of their former homeland.

Why is Ezra so important?

The book of Ezra provides a much-needed link in the historical record of the Israelite people. It provides an account of the Jews' regathering, of their struggle to survive and to rebuild what had been destroyed. Through his narrative, Ezra declared that God had not forgotten them.

In the book of Ezra, we witness the rebuilding of the new temple, the unification of the returning tribes as they shared common struggles and were challenged to work together. Later, after the original remnant had stopped work on the city walls and spiritual apathy ruled, Ezra arrived with another two thousand people and sparked a spiritual revival. By the end of the book, Israel had renewed its covenant with God and had begun acting in obedience to Him.

Ezra also contains one of the great intercessory prayers of the Bible (Ezra 9:5-15; see Daniel 9 and Nehemiah 9 for others). .

Ezra's narrative reveals two main issues faced by the returning exiles: (1) the struggle to restore the temple (Ezra 1:1-6:22) and (2) the need for spiritual reform (7:1-10:44). Both were necessary in order for the people to renew their fellowship with the Lord.

Traditional view of Ezra in the new temple

A broader theological purpose is also revealed: God keeps His promises. Through the prophets, God had announced that His chosen people would return to their land after a seventy-year exile. Ezra's account proclaims that God kept His word, and shows that when God's people remained faithful to Him, He would continue to bless them. His account emphasizes the importance of temple and proper worship.

Nehemiah

We meet Nehemiah serving in the Persian royal court as the personal cupbearer to King Artaxerxes (Nehemiah 1:11-2:1). This prestigious position reveals something of Nehemiah's upright character and statuys. Though he remained in Persia after the exiles had been allowed to go home, he was highly interested in the state of affairs in Judah (his brother Hanani [1:2] had returned there earlier).

The book of Nehemiah opens in the Persian city of Susa in the year 444 BC. Later that year, Nehemiah travelled to Israel, leading the third of three returns by the Jewish people following their exile in Babylon. (The previous chapter on Ezra describes the earlier two returns.) Most of the book centres on events in Jerusalem. The narrative concludes around the year 430 BC, and scholars believe the book was written shortly thereafter.

Nehemiah is the last historical book of the Old Testament. The prophet Malachi was a contemporary of Nehemiah.

Why is Nehemiah so important?

Nehemiah was not a priest like Ezra nor a prophet like Malachi. He served the Persian king in a secular position before leading a group of Jews to Jerusalem in order to rebuild the city walls. Nehemiah's expertise in the king's court equipped him adequately for the political and physical reconstruction necessary for the remnant to survive.

Under Nehemiah's leadership, the Jews withstood opposition and came together to accomplish their goal. Nehemiah led by example, giving up a respected position in a palace for hard labor in a politically insignificant district. He partnered with Ezra to solidify the political and spiritual foundations of the people. Nehemiah's humility before God (see his moving intercessory prayers in chapters 1 and 9) provided an example for the people. Nehemiah did not claim glory for himself but always gave God the credit for his successes.

Nehemiah recorded the reconstruction of the wall of Jerusalem. Together, he and Ezra, who led the spiritual revival of the people, directed the political and religious restoration of the Jews in their homeland after the Babylonian captivity.

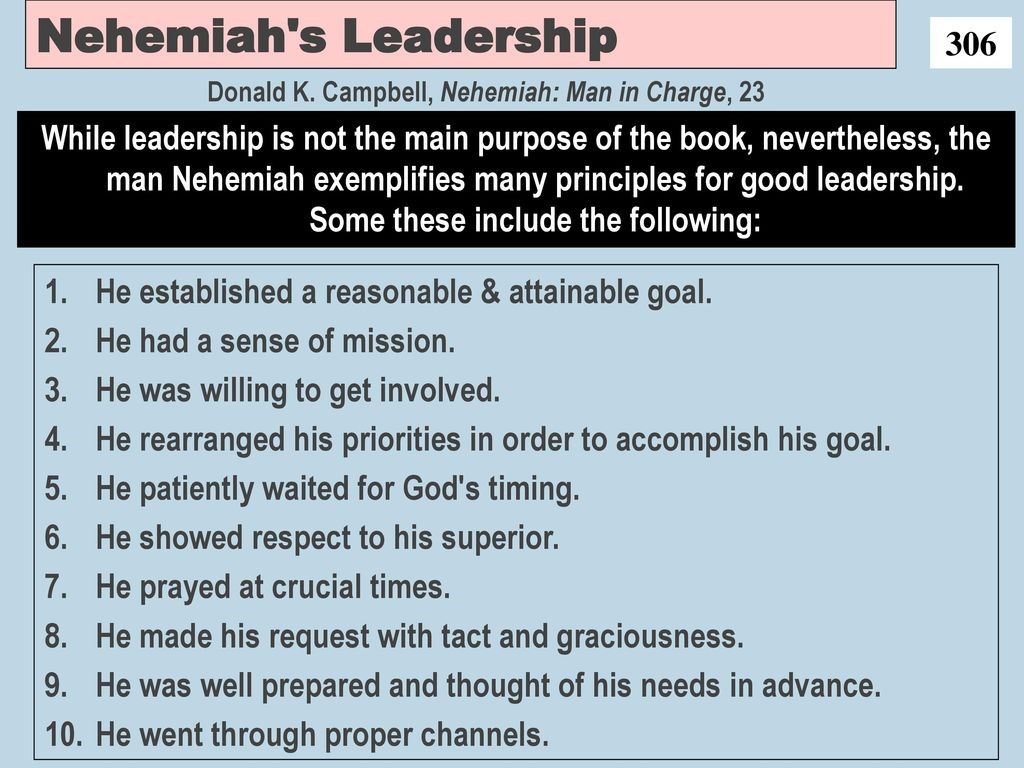

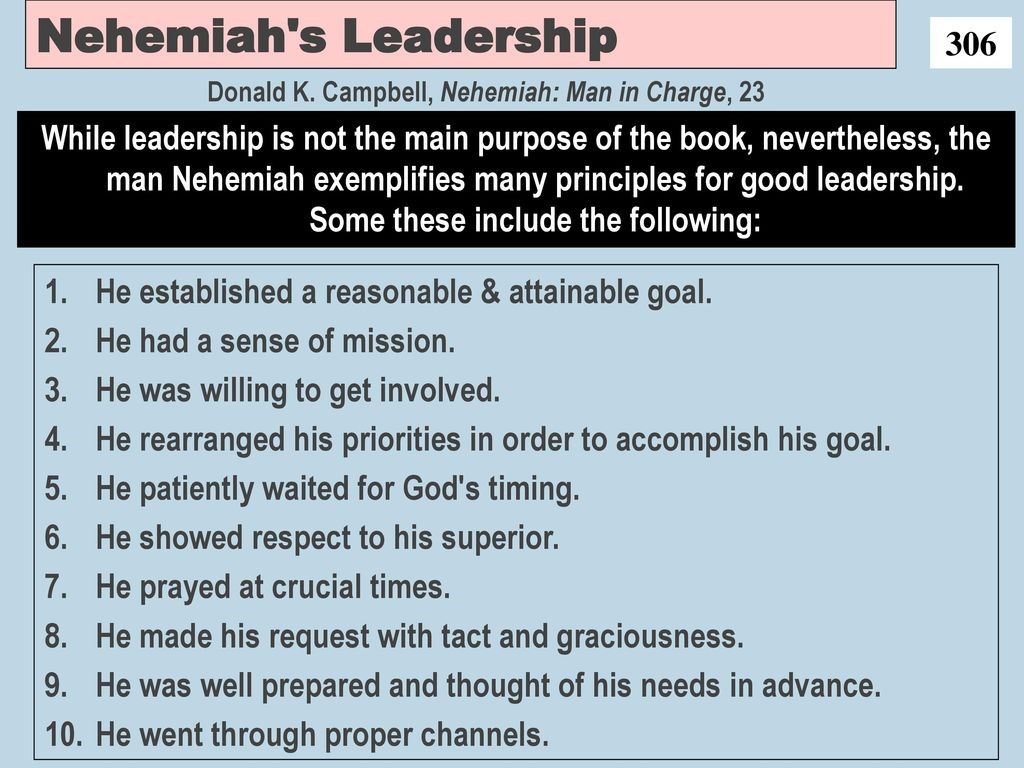

Nehemiah's leadership proved crucial to the Jews' spiritual advancement.

See John White's book, Excellence in Leadership, which draws on Nehemiah's life (available from Amazon or free download).

Nehemiah overcame great opposition from outsiders as well as internal turmoil and debilitating social stratification. Nehemiah exercised administrative skills in his strategy to use half the people for building while the other half kept watch for the Samaritans who, under an official named Sanballat, threatened to attack them (Nehemiah 4-7). Nehemiah had received permission to return to Jerusalem to rebuild the wall about the city; however, Sanballat, Tobiah, and Geshem campaigned against Nehemiah and those who were trying to rebuild the wall of Jerusalem; however, they failed in their attempts to stall and frustrate the work.

As governor, Nehemiah negotiated peace among the Jews who were unhappy with the burden of Persian taxes. He exhibited a steadfast determination to complete his goals. Accomplishing those goals resulted in a people encouraged, renewed, and excited about their future.

Nehemiah served in secular offices, using his position to bring back to the Jews a strong sense of order, stability, civic responsibility and focus on God. The book of Nehemiah shows us the significant impact one individual can have on a nation.

Leadership lessons from Nehemiah

Malachi

Malachi, whose name means "my messenger," spoke to the Israelites after their return from exile. The theological message of the book can be summed up in one sentence: the Great King will come not only to judge his people, but also to bless and restore them. Malachi starts out by describing how and where the people had failed God (yet again - had the exile/restoration not taught them anything?), but promises renewal if they will return to Him with genuine hearts.

By the time of Malachi, the people of Judah had been back in the land for more than a hundred years and were looking for the blessings they expected to receive when they first returned. Though the temple had been rebuilt, the zeal of those early returning Israelites gave way to apathy toward the things of God. This led to corruption among the priesthood and a spiritual lethargy among the people.

Malachi came along at a time when the people were struggling to believe that God loved them (Malachi 1:2). They focused on their circumstances and refused to account for the impacts of their sin. Through Malachi, God told the people where they had fallen short of their covenant with Him. If they hoped to see changes, they needed to take responsibility for their actions and serve God faithfully according to the promise their fathers had made to God.

After Malachi (in our Bibles), there is a silent "inter-Testamental" period of 400 years before the coming of Jesus Christ.

Elijah

Malachi connects the "messenger of the covenant" with Elijah. But who was he? In the OT, Elijah was seen as an archetypal representative of the prophets. He confronted religious and political leaders in God's name. He preached about repentance in the face of divine judgement. He demonstrated his message with power. He re-appeared , with Moses, on the Mount of Transfiguration with Jesus . When asked about the identity of the Elijah who was to come, Jesus pointed to John the Baptist (Matthew 11:7-15). The early church accepted this fulfilment as well, as a forerunner to the coming of the Messiah (Jesus). (Remember, this was still the Bible that Jesus and the earl Christians read - with a new angle that Malachi predicted.)

Reflection

- Nehemiah was not a professional priest. God uses all manner of people in all manner of places doing all manner of work. Do you feel you must be "in ministry" in order to serve God? Be encouraged; He is not limited by your vocation. God has placed you where you are for a purpose.

- God moved the hearts of secular rulers (Cyrus, Darius, and Artaxerxes) to allow, even encourage and help, the Jewish people to return home. He used these unlikely allies to fulfil His promises of restoration for His chosen people. Have you encountered unlikely sources of blessing? Have you wondered how God can really work all things together for the good of those who are called by His name (Romans 8:28)? Take time today to acknowledge God's sovereignty and mercy in your life. Recommit to Him your trust, your love, and your obedience.

- Nehemiah's enemies sought to draw him away from the work for "talks". They even caused the work to stop for a period, using what we would term "dirty tricks". Listen to Nehemiah's response: "I realized they were plotting to harm me, so I replied by sending this message to them: "I am engaged in a great work, so I can't come. Why should I stop working to come and meet with you?". Four times they sent the same message, and each time Nehemiah gave the same reply.

- "This is what the Lord says to Zerubbabel: It is not by force nor by strength, but by my Spirit, says the Lord of Heaven's Armies" (Zech 4:6). Build your life on this promise.

- Malachi prophesied "Look, I am sending you the prophet Elijah before the great and dreadful day of the Lord arrives. His preaching will turn the hearts of fathers to their children, and the hearts of children to their fathers." God wants to turn the hearts of the fathers to their children and vice versa. What does this mean in our generation?